Border as Refuge Interview

KoozArch

MArch Thesis Project

Advisor: Catherine Venart

Dalhousie, Architecture

2020

Project Description

The project examines the relationship between the rise in global refugees and current prohibitive migration policies. Due to this Canada is facing unprecedented rates of irregular asylum claims at the U.S. border. Like the Underground Railroad, the project provides migrants a network of “safe houses” in their search for freedom. Presently, most migrants travel through NYC and cross irregularly (not at an official port of entry) at Roxham Road, NY. It is at Roxham Road, a site straddling Canada and the U.S., that migrants are apprehended, processed, sent to shelters, and placed into a backed-up asylum system. The project provides sanctuary along the route by humanizing the irregular border crossing system. Border Refuge inverts the notion of borders as elements of division and transforms it into a tool for connection and inclusion. Clandestine interventions are inserted into the existing urban fabric, along the route from NYC to the border. These covert hideaways create an altered reality for migrants as they seek Canadian status.

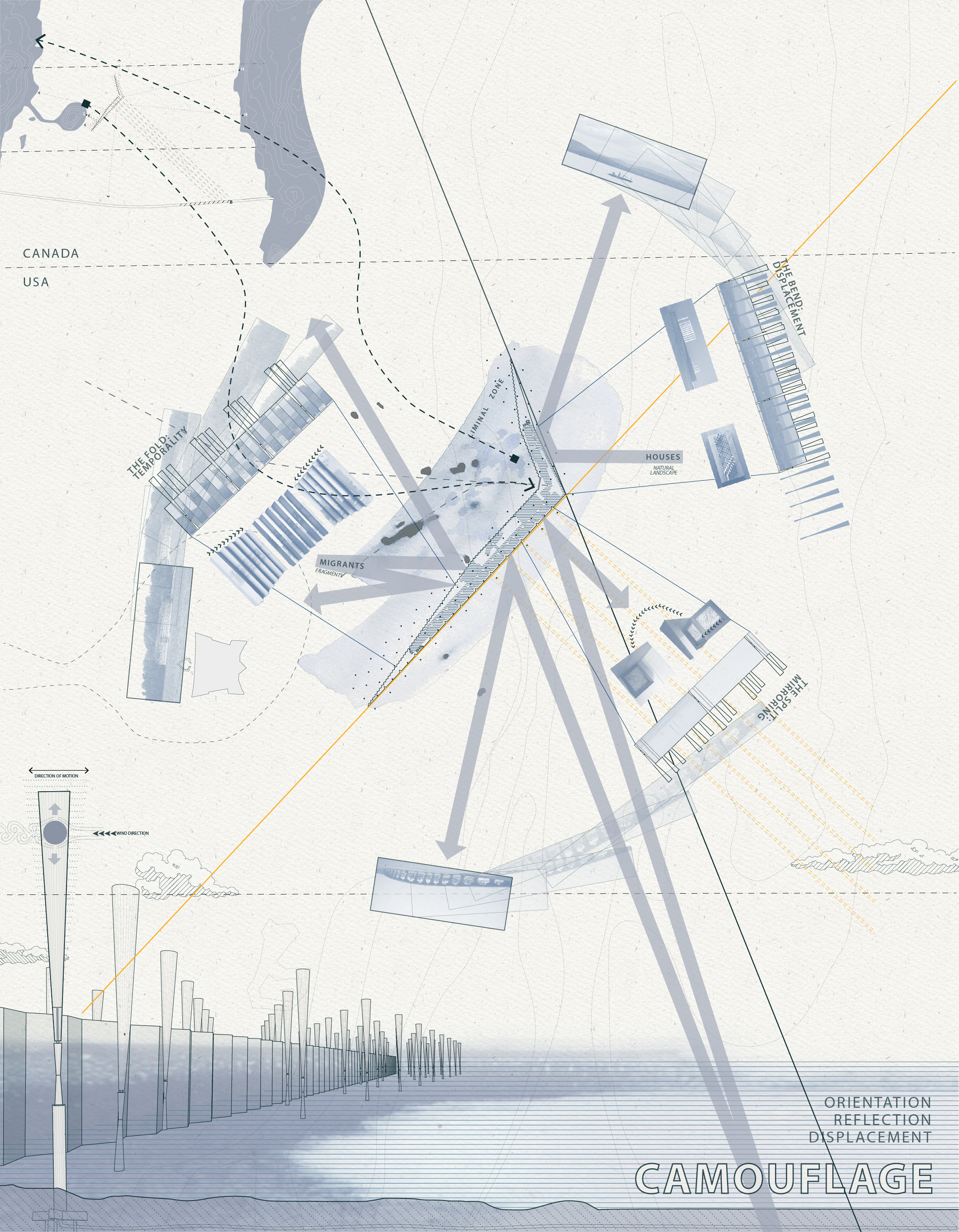

There are two sites of resistance within the project: Billboard Station and Border Refuge. Within these sites, three modes of resistance (location, camouflage, and escapability) are tested. The Billboard Stations inhabit the bones of existing billboards to create covert overnight shelters. The stations have thickened walls to provide zones for surveillance, dwelling, and escape. The inhabitation of the Canada – U.S border uses a speculative approach to expand the liminality. The island refuge is hidden in plain sight. Those in opposition only see landscape and those who seek protection receive sanctuary. This was tested with location (within a river) and camouflage using mimesis (form) and crypsis (image). Camouflage was employed through the wind farm and the use of the mirror. The connection between fantasy and reality occurs in the mirror. The exterior acts as a disguise and allowed for experimentation of the three modes of resistance. The construction of the mirrored wall also acted functionally to enclose and protect migrants. While the interior was designed with careful thought to migrant needs, material comfort, and light.

What prompted the project?

As the daughter of an asylum seeker, I have always paid attention to issues surrounding immigration and asylum. Around the 2016 U.S. election migrants began to cross into Canada by the thousands, and stories of their dangerous journeys made headlines. Numerous crossers had lost limbs from frostbite because of the unforgiving landscape that bridges both nations. These stories of hope and desperation prompted me to travel along the Canadian/American border and visit the sites that had high incidences of irregular migrant crossings.

On the research trip, I looked at spatial, environmental, and social contexts such as landscape, industry, and ICE cooperation to understand what drove migrants to cross and why at those specific destinations. Mapping migrant stories lead to the discovery that most migrants fly to NYC and travel (walk, bus, or taxi) to Roxham Road, NY. Bearing witness to the crossing conditions at Roxham Road was an extremely emotional experience. I witnessed a 14-year-old girl, who traveled alone from Ethiopia, arrive at the dirt ditch separating both countries in utter fear. There is no dignity for asylum seekers, especially at the hands of the RCMP. Refugees decide to cross irregularly out of desperation, they have no other choice. Border conditions should not compound their fear.

What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

The project began as an inquiry as to how architecture and the liminal could be used to reimagine inhabitable conditions for refugees seeking asylum. To address this question, numerous perspectives needed to be challenged. I challenged the border as a tool of separation, the policies that force irregular migrants into precarious positions, and the methods (long wait times, holding migrants in prisons, etc.) that Canada and the U.S. use to process refugees, placing them in a state of limbo. Border as Refuge: Inhabiting the Liminal attempted to tackle these challenges by merging that which is both elusive/imaginary, with the pragmatic and very real needs of migrants.

How does the project challenge the common definition of border?

The project challenges the use of borders as a means of division and segregation and proposes it as a place of encounter. The border is not just a line where geographical, political, and social conditions converge, but it is a liminal space rife with opportunity. By inhabiting the two liminal sites of resistance, a threshold where migrants can seek refuge is created. Using Foucault’s notion of heterotopias, the sanctuaries act like counter-sites, a physical manifestation of utopia where ideas are represented, contested, and inverted.

The first site of resistance is the Billboard Stations, located between Plattsburgh and the border. This zone is typically dangerous for migrants because of high ICE presence. The use of existing billboards helped with deception and camouflage. From those unsuspecting, the billboard appears as mundane marketing; however, to those in need, it provides a safe and covert place to sleep. There are two methods of camouflage developed within the project: crypsis and mimesis. Crypsis is a method that employs architecture to distort and obscure while mimesis (to mimic) is a method of deception that disguises the architecture as something else. To help with concealment, inhabitation occurs within the walls of the billboard, allowing for events to take place within the in-between. Inhabited walls were implemented to unite pertinent polarities: inside-outside, seen-hidden, and fear-freedom.

The second site of resistance is the Border Refuge, positioned in the middle of the Richelieu River between Canada and the U.S. Asylum seekers have autonomy over this refuge, as they await due process. The river is used as a framework to situate migrants, suspending them in space and time. The site lies at the convergence point of historic sightlines from Mount Royal, Quebec (MR), and Dannemora Mountain, New York (DM). Four distinct zones were created from the sightlines: visible from MR, visible from DM, visible by both, and the invisible zone. Border Refuge uses these zones and sightlines as tools for placement, alignment, and programming. The refuge uses water and mirrors as tools to blur the site's edges. All the facades are two-way mirrors that reflect its surroundings, merging themselves into the landscape. The convergence of the four zones and its relation to the landscape required three different treatments for the mirrored façades. The Fold, the Bend, and the Split each help conceal Border Refuge in different ways. Foucault described the mirror as a metaphor for heterotopia. “It is a placeless place... [you] see yourself where [you] are not.” The facade simultaneously reflects and positions migrants into their future.

How and to what extent has the current pandemic exacerbated the migration crisis globally?

Before the pandemic refugees and irregular migrants were already very disregarded. With the presence of COVID-19, these vulnerabilities are being exacerbated. Refugee camps across the globe suffer from overcrowded conditions and provide migrants with little access to hygiene and sanitation facilities. With poor access to water, space to social distance, or healthcare they are susceptible to contracting and spreading disease. These issues of sanitation and hygiene are also prevalent in detention centers. The U.S. is witnessing detainees and employees battle the pandemic, which is further compounded by the absence of adequate personal protection equipment.

With racial tensions at an all-time high, rising xenophobia, and increased risk of detainment and deportation for migrants, individuals have looked to Canada for safety. COVID-19 is bringing increased danger to irregular migrants because Canada has closed the irregular border crossing site at Roxham Road. At the onset of the pandemic, all of Canada’s borders were closed except for “essential” travel. This not only prevents anyone from seeking asylum, but it prevents the most marginalized of our population from seeking safety. I would argue that nothing could be more “essential” than fleeing violence. Everyone should have the right to safety. The plan to introduce mandatory quarantine that the Canadian government abandoned should be implemented and the irregular border crossing at Roxham Road should remain open to prevent asylum seekers from crossing at more dangerous locations.

What are in your opinion the greatest shortcomings from a governmental, social, and economic perspective in dealing with this situation?

There are substantial weaknesses in the organizational and operational structures of the Canadian and American asylum systems. Following the 2016 U.S. federal election, Canada faced drastic increases in irregular border crossings. The trend is twofold; first, the world is facing a rise in xenophobia which, combined with a biased portrayal of migrants, has fueled anti-immigrant rhetoric. Societies' deep-rooted obsession with security and defense has constructed many of the obstacles refugees face. Second, the creation of policies such as the Muslim Ban and the expiration of Temporary Protected Status have further terrorized migrants and incentivize them to travel north and seek asylum in Canada. These political measures and threats have garnered so much fear that thousands have crossed into Canada and quickly overwhelmed the system. Under the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA), refugees who cross at regular ports of entry are told to return to the United States, a “safe country.” To prevent this, migrants have found a loophole in the STCA and are crossing at irregular points along the border. Canada urgently needs to make changes to the agreement to protect the safety of refugees.

What is our role as Architects and citizens of society? Architecture has focused on the incorporation of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers into the existing urban fabric of cities. While this is an important phase, it is one in a series. It should not, in my opinion, be the sole focus. The project attempts to illustrate the other phases and spatial conditions that migrants and refugees are forced to navigate: The context they are forced to abandon, the diverse liminal spaces they transition through, and the context into which are incorporated. We need to acknowledge that there are different temporal scales to each of these phases. Currently, society defines the transition period as temporary, yet migrants spend an average of 17 years in encampments. How can 17 years be viewed as temporary?

How does the project approach the architect's role and power in relation to the migration crisis?

The project is a protest of not only current prohibitive migration policies but of the entire system. Architecture should reimagine our role and agency concerning these systems. I believe we must counter and resist; resist a system that oppresses others and that uses space to commit violence. The project does not attempt to change the system from the periphery or from within (it would have been naïve to attempt to circumvent a system that architecture has actively participated in). Rather the project recognizes that the system as it is must be abolished, there can be no change to a system that is functioning as historically intended. By utilizing what I term architectural modes of resistance to subvert the status quo, heterotopias are created to facilitate a network of sanctuaries at points of conflict to help migrants seek sanctuary in unfamiliar environments.

What is for you the architect's most important tool?

The ability to transfer our voice, our experiences, and our understanding of the world onto paper, analog or otherwise. We are “optimistic researchers” who have a unique ability to transition from words, text, data, and built form to illustration. Our language is that of the image. In a time of social and political uncertainty, I think it is important that we continue to distill and document our environment as a method for speculating, problem-solving, and testing ideas. By documenting untold stories and advocating for marginalized groups, we are creating a collective historical catalog that cannot be overlooked.

KoozArch

MArch Thesis Project

Advisor: Catherine Venart

Dalhousie, Architecture

2020

Project Description

The project examines the relationship between the rise in global refugees and current prohibitive migration policies. Due to this Canada is facing unprecedented rates of irregular asylum claims at the U.S. border. Like the Underground Railroad, the project provides migrants a network of “safe houses” in their search for freedom. Presently, most migrants travel through NYC and cross irregularly (not at an official port of entry) at Roxham Road, NY. It is at Roxham Road, a site straddling Canada and the U.S., that migrants are apprehended, processed, sent to shelters, and placed into a backed-up asylum system. The project provides sanctuary along the route by humanizing the irregular border crossing system. Border Refuge inverts the notion of borders as elements of division and transforms it into a tool for connection and inclusion. Clandestine interventions are inserted into the existing urban fabric, along the route from NYC to the border. These covert hideaways create an altered reality for migrants as they seek Canadian status.

There are two sites of resistance within the project: Billboard Station and Border Refuge. Within these sites, three modes of resistance (location, camouflage, and escapability) are tested. The Billboard Stations inhabit the bones of existing billboards to create covert overnight shelters. The stations have thickened walls to provide zones for surveillance, dwelling, and escape. The inhabitation of the Canada – U.S border uses a speculative approach to expand the liminality. The island refuge is hidden in plain sight. Those in opposition only see landscape and those who seek protection receive sanctuary. This was tested with location (within a river) and camouflage using mimesis (form) and crypsis (image). Camouflage was employed through the wind farm and the use of the mirror. The connection between fantasy and reality occurs in the mirror. The exterior acts as a disguise and allowed for experimentation of the three modes of resistance. The construction of the mirrored wall also acted functionally to enclose and protect migrants. While the interior was designed with careful thought to migrant needs, material comfort, and light.

What prompted the project?

As the daughter of an asylum seeker, I have always paid attention to issues surrounding immigration and asylum. Around the 2016 U.S. election migrants began to cross into Canada by the thousands, and stories of their dangerous journeys made headlines. Numerous crossers had lost limbs from frostbite because of the unforgiving landscape that bridges both nations. These stories of hope and desperation prompted me to travel along the Canadian/American border and visit the sites that had high incidences of irregular migrant crossings.

On the research trip, I looked at spatial, environmental, and social contexts such as landscape, industry, and ICE cooperation to understand what drove migrants to cross and why at those specific destinations. Mapping migrant stories lead to the discovery that most migrants fly to NYC and travel (walk, bus, or taxi) to Roxham Road, NY. Bearing witness to the crossing conditions at Roxham Road was an extremely emotional experience. I witnessed a 14-year-old girl, who traveled alone from Ethiopia, arrive at the dirt ditch separating both countries in utter fear. There is no dignity for asylum seekers, especially at the hands of the RCMP. Refugees decide to cross irregularly out of desperation, they have no other choice. Border conditions should not compound their fear.

What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

The project began as an inquiry as to how architecture and the liminal could be used to reimagine inhabitable conditions for refugees seeking asylum. To address this question, numerous perspectives needed to be challenged. I challenged the border as a tool of separation, the policies that force irregular migrants into precarious positions, and the methods (long wait times, holding migrants in prisons, etc.) that Canada and the U.S. use to process refugees, placing them in a state of limbo. Border as Refuge: Inhabiting the Liminal attempted to tackle these challenges by merging that which is both elusive/imaginary, with the pragmatic and very real needs of migrants.

How does the project challenge the common definition of border?

The project challenges the use of borders as a means of division and segregation and proposes it as a place of encounter. The border is not just a line where geographical, political, and social conditions converge, but it is a liminal space rife with opportunity. By inhabiting the two liminal sites of resistance, a threshold where migrants can seek refuge is created. Using Foucault’s notion of heterotopias, the sanctuaries act like counter-sites, a physical manifestation of utopia where ideas are represented, contested, and inverted.

The first site of resistance is the Billboard Stations, located between Plattsburgh and the border. This zone is typically dangerous for migrants because of high ICE presence. The use of existing billboards helped with deception and camouflage. From those unsuspecting, the billboard appears as mundane marketing; however, to those in need, it provides a safe and covert place to sleep. There are two methods of camouflage developed within the project: crypsis and mimesis. Crypsis is a method that employs architecture to distort and obscure while mimesis (to mimic) is a method of deception that disguises the architecture as something else. To help with concealment, inhabitation occurs within the walls of the billboard, allowing for events to take place within the in-between. Inhabited walls were implemented to unite pertinent polarities: inside-outside, seen-hidden, and fear-freedom.

The second site of resistance is the Border Refuge, positioned in the middle of the Richelieu River between Canada and the U.S. Asylum seekers have autonomy over this refuge, as they await due process. The river is used as a framework to situate migrants, suspending them in space and time. The site lies at the convergence point of historic sightlines from Mount Royal, Quebec (MR), and Dannemora Mountain, New York (DM). Four distinct zones were created from the sightlines: visible from MR, visible from DM, visible by both, and the invisible zone. Border Refuge uses these zones and sightlines as tools for placement, alignment, and programming. The refuge uses water and mirrors as tools to blur the site's edges. All the facades are two-way mirrors that reflect its surroundings, merging themselves into the landscape. The convergence of the four zones and its relation to the landscape required three different treatments for the mirrored façades. The Fold, the Bend, and the Split each help conceal Border Refuge in different ways. Foucault described the mirror as a metaphor for heterotopia. “It is a placeless place... [you] see yourself where [you] are not.” The facade simultaneously reflects and positions migrants into their future.

How and to what extent has the current pandemic exacerbated the migration crisis globally?

Before the pandemic refugees and irregular migrants were already very disregarded. With the presence of COVID-19, these vulnerabilities are being exacerbated. Refugee camps across the globe suffer from overcrowded conditions and provide migrants with little access to hygiene and sanitation facilities. With poor access to water, space to social distance, or healthcare they are susceptible to contracting and spreading disease. These issues of sanitation and hygiene are also prevalent in detention centers. The U.S. is witnessing detainees and employees battle the pandemic, which is further compounded by the absence of adequate personal protection equipment.

With racial tensions at an all-time high, rising xenophobia, and increased risk of detainment and deportation for migrants, individuals have looked to Canada for safety. COVID-19 is bringing increased danger to irregular migrants because Canada has closed the irregular border crossing site at Roxham Road. At the onset of the pandemic, all of Canada’s borders were closed except for “essential” travel. This not only prevents anyone from seeking asylum, but it prevents the most marginalized of our population from seeking safety. I would argue that nothing could be more “essential” than fleeing violence. Everyone should have the right to safety. The plan to introduce mandatory quarantine that the Canadian government abandoned should be implemented and the irregular border crossing at Roxham Road should remain open to prevent asylum seekers from crossing at more dangerous locations.

What are in your opinion the greatest shortcomings from a governmental, social, and economic perspective in dealing with this situation?

There are substantial weaknesses in the organizational and operational structures of the Canadian and American asylum systems. Following the 2016 U.S. federal election, Canada faced drastic increases in irregular border crossings. The trend is twofold; first, the world is facing a rise in xenophobia which, combined with a biased portrayal of migrants, has fueled anti-immigrant rhetoric. Societies' deep-rooted obsession with security and defense has constructed many of the obstacles refugees face. Second, the creation of policies such as the Muslim Ban and the expiration of Temporary Protected Status have further terrorized migrants and incentivize them to travel north and seek asylum in Canada. These political measures and threats have garnered so much fear that thousands have crossed into Canada and quickly overwhelmed the system. Under the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA), refugees who cross at regular ports of entry are told to return to the United States, a “safe country.” To prevent this, migrants have found a loophole in the STCA and are crossing at irregular points along the border. Canada urgently needs to make changes to the agreement to protect the safety of refugees.

What is our role as Architects and citizens of society? Architecture has focused on the incorporation of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers into the existing urban fabric of cities. While this is an important phase, it is one in a series. It should not, in my opinion, be the sole focus. The project attempts to illustrate the other phases and spatial conditions that migrants and refugees are forced to navigate: The context they are forced to abandon, the diverse liminal spaces they transition through, and the context into which are incorporated. We need to acknowledge that there are different temporal scales to each of these phases. Currently, society defines the transition period as temporary, yet migrants spend an average of 17 years in encampments. How can 17 years be viewed as temporary?

How does the project approach the architect's role and power in relation to the migration crisis?

The project is a protest of not only current prohibitive migration policies but of the entire system. Architecture should reimagine our role and agency concerning these systems. I believe we must counter and resist; resist a system that oppresses others and that uses space to commit violence. The project does not attempt to change the system from the periphery or from within (it would have been naïve to attempt to circumvent a system that architecture has actively participated in). Rather the project recognizes that the system as it is must be abolished, there can be no change to a system that is functioning as historically intended. By utilizing what I term architectural modes of resistance to subvert the status quo, heterotopias are created to facilitate a network of sanctuaries at points of conflict to help migrants seek sanctuary in unfamiliar environments.

What is for you the architect's most important tool?

The ability to transfer our voice, our experiences, and our understanding of the world onto paper, analog or otherwise. We are “optimistic researchers” who have a unique ability to transition from words, text, data, and built form to illustration. Our language is that of the image. In a time of social and political uncertainty, I think it is important that we continue to distill and document our environment as a method for speculating, problem-solving, and testing ideas. By documenting untold stories and advocating for marginalized groups, we are creating a collective historical catalog that cannot be overlooked.